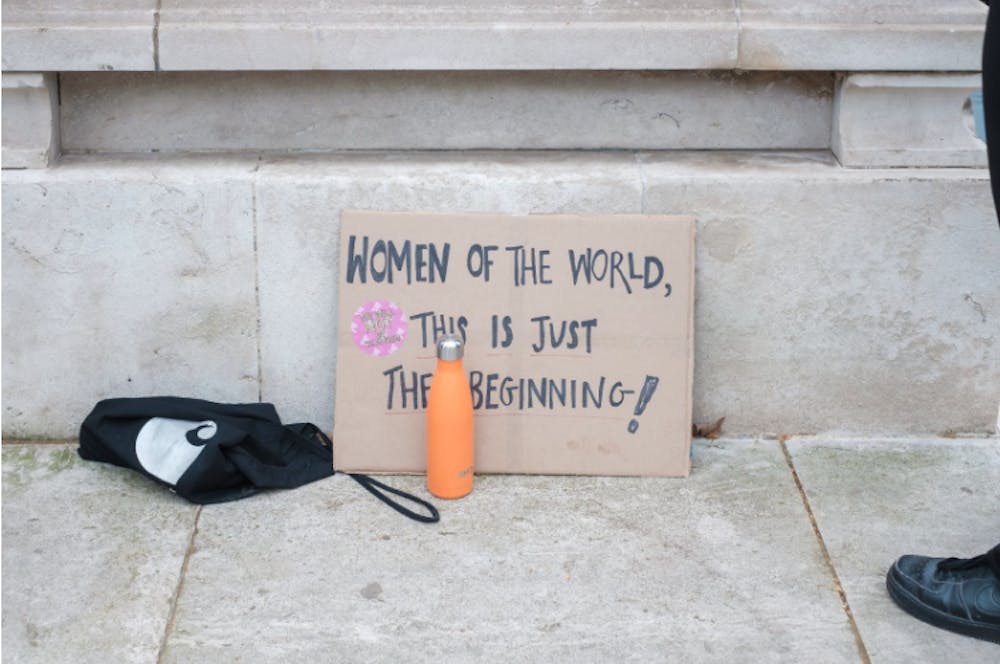

The onset of warm weather has brought us yet another opportunity to confront the conditions of women everywhere.

This past Women’s History Month in March launched superficial Instagram story campaigns full of recycled infographics and meaningless platitudes calling for celebration and awareness but not much else. Though sardonic and skeptical, pessimism towards the feminist movement as a whole is not uncommon. Since its start in the 19th-century, the modern women’s movement has debatably failed to represent the interests of marginalized women and aided towards advocating for the rights of middle-class white women.

The waves of feminism, which have been lead by white women, advocate for the prioritization of gender equality and target the structure of capitalism but lack the capacity to advocate for Black and women of color who have been historically disenfranchised by the very structures that dehumanize and systemically exploit Black women, women of color, and other intersectional identities.

The start of feminism in America revolved around women’s suffrage. From Seneca Falls to the ratification of the 19th, the movement was led primarily by white women such as Elizabeth Stanton and Susan B. Anthony—both of whom sided with white nationalists to oppose Black suffrage after the 15th Amendment.

The mid 20th-century consisted of several de jure victories for women, including the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Title IX in 1972, and Roe v. Wade in 1973. The Feminist Mystique by Betty Friedan (1963) additionally helped to democratize messages of equality by making them available to a wider audience. The wider audience, however, was middle-class white women; thus the motives of the second wave were centered around the interests of white women.

During the same time, Black women were fighting forms of discrimination that manifested in disproportionate rates of poverty, job discrimination, in addition to the lack of intersectionality within the Civil Rights Movement. Black women such as Ella Baker, Daisy Bates, and Dorothy Height were crucial to the momentum and organization of the Civil Rights Movement; however, they were never recognized and the efforts of Black women were simply absorbed, while the calls for intersectional equality were ignored. The lack of both de jure and de facto equality led to the “Black Feminist” movement, which arose through figures such as Angela Davis, bell hooks, and Alice Walker. The countermovement put intersectionality at the crux of feminism; bell hooks said that “although the focus is on the Black female, our struggle for liberation has significance only if it takes place within a feminist movement that has as its fundamental goal the liberation of all people.”

The third wave has a timeline that is strongly debated but is commonly understood to begin with Anita Hill’s sexual assault accusations to Clarence Thomas. It namely consists of an outpour of workplace discrimination, harassment, and disproportionate representation of men in positions of power. However, not everyone’s voices were heard. Hill’s voice as a Black woman was actively undermined by Thomas, who claimed that the accusations were intended to keep a Black man out of the Supreme Court. The unique compounding of racism and misogyny, or misogynoir, painted Hill as a ‘race traitor’ and left her defenseless in the face of racial and gendered stereotypes.

Throughout history, the feminist movement has embodied contradictions. The fourth wave is understood to be now, yet the conflict continues as the objectives of white women actively contribute to the oppression of intersectional women. As a time defined by growing awareness of intersectionality and interconnected systems of oppression, women of all intersections and identities should stop having to create movements of their own to be included within the continuum of liberation and equity.

Women of all intersections and identities should no longer be subject to the dichotomy of invisibility and hypervisibility. Hypervisibility reduces women from nuanced humans to a detrimental stereotype and prevents them from having their needs and wants met; Latina women are disproportionately represented as hypersexual beings, Black women as inherently hypermasculine, and Asian women as conquerable, docile figures. Though it seems relatively harmless, hypervisibility is the cause of many harmful disparities, including health inequity, job inequity, body exploitation, and more. Invisibility is when Black women are unable to profit off their creativity, with creators like Charli D’Amelio (net worth approx. 12-20 million) and Addison Rae (net worth approx. 5-20 million) building multi-million dollar platforms off of the invention of Jalaiah Harmon. Or when missing and murdered Black and Indigenous women, such as Lauren Smith-Fields, only garner instagram posts when white women, such as Gabby Petito, get a national investigation to their name.

According to the National Crime Information Center, almost a third of the 300,000 missing girls and women in the US last year were Black. Or when the consecutive murders of Christina Yuna Lee, Michelle Go, Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Soon Chung Park, Suncha Kim, and Yong Ae Yue aren’t investigated as hate crimes, despite claims that the fetishization of their Asian womanhood played a role in their murders. Or when the reports of forced sterilization of Mexican immigrant women detained by ICE at the border receive no attention in relation to reproductive issues and problems that directly affect white women.

Despite the assumption that liberation movements are inherently collectivist, the feminism and women’s movement in America has proved to center around individualism, with white women throughout history exploiting platforms given to them by their whiteness. The ability of white women to primarily identify with their womanhood because of its marginal nature is a privilege within itself, and has and continues to allow the women’s movement to ignore double standards and nuances of systemic obstructions that are intersectional in nature.

Only when the concerns of all women are addressed and all people are liberated will women be liberated and the will feminist movement no longer stand in contradiction with itself. This March then, take a moment to learn the true history of feminism in the United States, meaning the way that Black women and women of color have had to continously fight twice as hard because of their political, economic and social exclusion.